[This is another long response to a post on Albert Wenger’s blog.]

Thanks for writing about this, Albert. The issue has been on my mind lately as well.

I’ve read at least a half-dozen pieces full of hand wringing about the economics of streaming. It’s certainly an important issue for the future of music. Streaming provides by far the best user experience I’ve found, and dominant experiences have a habit of dominating industries.

I’d like to elaborate a bit on your themes:

Transformation of the Label:

We all sort of take it for granted that there is such a thing as “the music industry” that is defined as the oligopoly of major labels. But the labels only exist in the first place because for a century the only way to transmit music to consumers was to manufacture, distribute, and sell pieces of plastic. Promotion, A&R, financing etc. came along for the ride mostly because of the economics of vertical integration.

Now that the cost to transmit music to consumers has fallen to literally zero, labels have lost their core raison d’être. Normally an industry without a customer would go the way of Kodak. But our political system has decided that “To promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries” translates into “let’s incentivize Mr. Zombie Walt Disney to create more memorable characters in the past by extending copyrights another 20 years.”

But as we wait for the expensive legal life-support to gradually fail, the “peripheral” functions of labels are already becoming their core business. I’ll discuss below how they can add real value by focusing on those functions.

Dealing With Consumer Surplus:

By removing the cost of distribution, the internet gives any artist (including an obscure horse-dancing Korean rapper) an enormous audience while simultaneously forcing them to compete against the whole history of recorded music. These conditions exponentially magnify the marginal rewards of excellence, which is exactly what we’re seeing in music (and in Hollywood, and in finance, and in technology…)

All of the dismay over artists’ earnings focuses on acts like Zoe Keating, Galaxie 500, or Grizzly Bear. Those three artists have one thing in common: they’re obscure (at least relatively – they have 1,160,623, 4,538,748 and 36,486,805 total song listens on Last.fm respectively.) But you won’t read any articles complaining about how little Lady Gaga or Rihanna are earning (180,396,404 and 120,265,212 plays respectively, and that’s probably a vast understatement because the average Rihanna fan is much less likely to use Last.fm)

It shows a curious lack of historical perspective to complain that the Zoe Keatings of the world can barely earn a living now. The “now” implies that they would have been wealthy in 1980; on the contrary, they would simply never have been signed by a label and would never have had any career, much less an only-modestly-lucrative one. How many of the unsigned D.I.Y. Punk or Metal bands from 1982 ever earned even $30k/year from their music?

Personally, I like Zoe Keating and Grizzly Bear. I’d probably buy tickets to their shows. But there is no way I would have paid $16 for one of their CD’s or iTunes albums after hearing them played once in a friend’s dorm room in 2006. And without viral promotion that cheap distribution allows, they probably never would have gotten off the ground.

The only way musicians have ever gotten rich is by having a ton of fans. And so labels have an opportunity to add a lot of value by becoming more like Hollywood managers/agents and helping musicians effectively use all the channels available to get more people listening to their music.

The Economics of Streaming:

There’s something awfully fishy about all the numbers that are being thrown around. If the average American spends $43/year on recorded music and a Spotify premium subscription costs $120/year, then streaming services are collecting more money per customer. So where does the money go? It’s clearly not staying with Spotify, which is nowhere close to turning a profit.

The answer (probably; the numbers aren’t public) is that the lion’s share of the money is going to major labels to bribe them into deigning to accept money for their back catalog, and the rest is going to disproportionately popular artists like Rihanna. Spotify streamed over 13 billion songs in 2012, of which Galaxie 500 represented 7,800 (i.e. 0.00006%).

In other words, streaming is actually making the total pot bigger. The problem isn’t with the amount of money – it’s with the distribution.

Distribution in Space and Time

“Long-tail” acts like Zoe Keating (who, as I mentioned above, probably could not even exist before digital music) are being hit with two economically wonky headwinds: first, streaming presents them with a cash flow crisis; second, bulk licensing inefficiently homogenizes pricing.

Cash flow:

An entrepreneur sells a widget for $400 and has the choice of collecting payment immediately or receiving $10/month every month for five years. Even though the second option eventually generates $600, most entrepreneurs will choose the first. Entrepreneurs are generally cash poor and prefer being able to pay bills now even if it means retiring a bit later.

Large corporations, on the other hand, can be exactly the opposite. GE has an entire branch (GE Capital) that provides financing to consumers so they can buy a washing machine now and pay for it gradually. By reaping profits slower, GE is able to sell substantially more in total.

Zoe Keating is in the same position as the entrepreneur. iTunes gives her a one-time upfront payment, whereas Spotify is an annuity. If we assume her earnings-per-song-play are the same (see below) then her total earnings over time should be the same.[1] But she can’t pay her rent with royalty checks from 2023.

But…actually she can. It’s time to call in the investment bankers. There are simple mathematical formulas to calculate the present value of an annuity. If an analyst can estimate how many times a song will be played in total over the next 20 years she can easily calculate the total earnings from those streams and write Zoe Keating a check for 85% of that amount by borrowing the money from a bank and eventually paying it back as the royalties come in.

So this is the second way labels can add value: by becoming investors. They can develop expertise in predicting long-term song popularity and market sizes (perhaps using some of that juicy big data) and then perform the financial engineering necessary for artists to cash out now (i.e. “provide an advance”). That’s always been an essential function of labels (and publishers) but streaming makes it both harder and more important.

Pricing homogeneity:

When everyone pays $16 for a CD, some buyers get a much better deal. Many consumers will listen to the CD once or twice and then consign it to a shelf. Some will listen to the CD one thousand times. That means the price-per-play of the CD varies from $16 all the way to 1.6 cents. But every customer still pays $16, of which ($16 * ~7%) ~= $1 goes to the artist. So artists are actually able to charge their casual fans a lot more (and also force them to pay for the ~50% of an album that’s usually filler.)

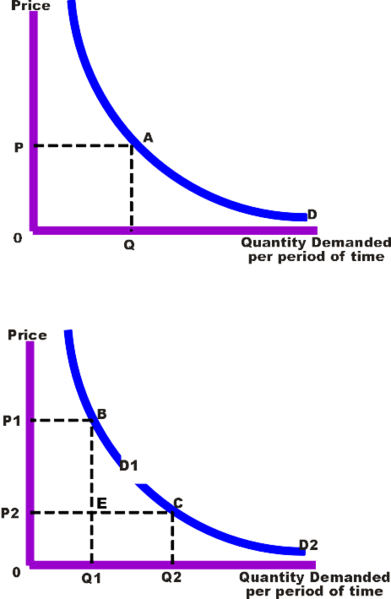

In streaming land, both of those advantages disappear. Consumers only pay for the actual product they want in the exact quantity they want. And crucially, they all pay the same price regardless of willingness to pay. That leads to a classic economic conundrum:

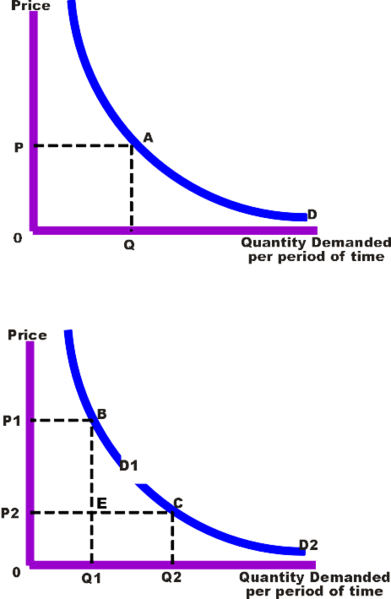

Even if artists do earn only 0.3 cents per stream of their songs, they can actually earn the same amount as they would from a (major label) CD sale if fans stream their albums ~50 times ($1 / ($.003 * 8 non-filler songs)). Most fans will never do that, but some will, and would even if they had to pay extra. If artists could charge different amounts to different fans, they could capture more of the demand curve and earn more money.

Price homogeneity is a hard nut to crack: one idea I discuss in an old blog post is to make subscriptions “modular” (e.g. pay extra to listen to the Beatles on Spotify) and dynamically re-price the modules based on demand and consumer profiles. But that’s probably too complicated to happen any time soon.

Kickstarting the Promised Land:

Kickstarter is extremely exciting because it fixes both wonkish economic problems in one swoop. If an artist can build a loyal fan base, she can use Kickstarter to transfer her earnings from future to present (even if no label or banker is willing to take the risk.) And she can effectively price discriminate by encouraging the most loyal/wealthy fans to pay a lot more. Plus, she can use the harvested contact info to engage with fans and encourage them to come to her shows and buy her t-shirts (or much more lucratively, her favorite brand of soap).

So in summary: a bigger pie logically has to mean a bigger meal. We just may have to wait for a few unwelcome uncles to leave the table.

If you like this post, please up-vote on Hacker News.

[1] I’m ignoring the effects of interest and inflation on the time value of money because it’s complicated and I’m assuming that streaming costs will grow over time at approximately the appropriate rate.